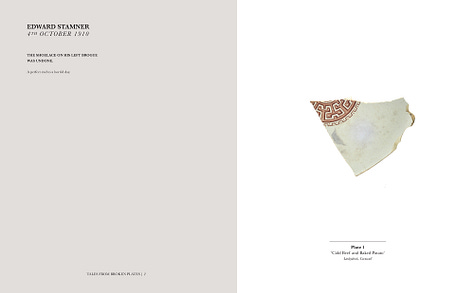

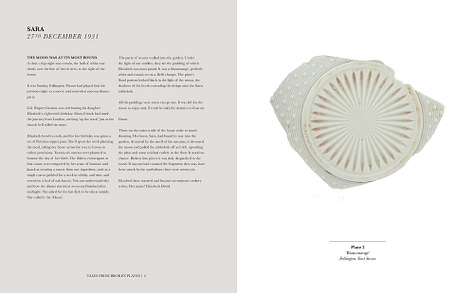

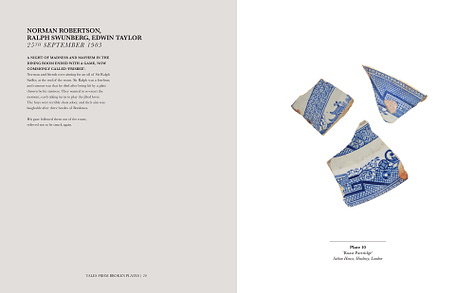

Broken plates

It’s taken me too long to shout about a special book I completed work on at the end of last year with the artist and writer, Mark Lawson Bell. Mark and I worked together closely on a restaurant book over a decade ago that never did make it to publication, but that’s perhaps a story for another day. For his own book, Mark had been scribbling away at a collection of stories for a long time. When first we spoke, it had a working title of Last Suppers and he was looking for a designer to help bring everything together into book form. Mark had collated a curious collection of fifty-two ‘imaginings’, creating a recipe book without any recipes. Each dish was named, but Mark would tell the stories of the plates, not the ‘suppers’ – specifically, of how each piece of ceramic ware would meet its demise. The inspiration for Mark’s idea was a growing collection of pottery ‘sherds’1, the found pieces of porcelain and earthenware debris that he had been picking up for many years whilst walking and wandering and mudlarking his way around the southern half of the British Isles. The idea was a simple one – how did these pieces of pottery, these fragments of once-domestic vessels, come to be where they were? One was embedded into a cliff face in Hastings. Others glinted from the riverbeds of London and Cornwall, their once-razor-sharp edges smoothed by the waters of the Thames and the Lerryn. The Biblical-sounding Last Suppers would be renamed Tales From Broken Plates and they are tales that are rich and clever and playful and melancholy. They read like Lewis Carroll one moment and a ‘Boy’s Own’ story the next, with the occasional gothic notes of Robert Louis Stevenson, not least in the-strychnine-laced final meal of Mr Philip Trotter (a supper of black pudding). The tales are inspired sometimes by the places where the sherds were discovered, others by the markings which decorated each new find. It was a pleasure to work with Mark again, to set all of his stories to page, and to bring his charmingly original idea to fruition. You can read and listen to a few of the stories over at Mark’s website, above. And you can look deeper into Mark’s uniquely alluring and artistic mind here.

The joy of index

Often, the index that finishes a book can inspire you to journey inside its pages in a way that the contents page that begins it cannot. For instance, this book next to me on the desk lists these subjects a few indexed steps apart:

Sisyphus 195-6

‘Soares, Bernardo’ (Fernando Pessoa) 131

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr 99, 100

Undoubtedly, not everyone’s cup of tea, but equivalent to tea with a custard cream on the side for me. Had that book’s blurb or introduction not already persuaded me to delve and read further, the discovery of such a cluster of indexed entries most certainly would. It’s a shame that indexes often don’t get the full appreciation they deserve from an editor and publisher. Having spent many years in and around publishing, I can shamefully admit to index neglect during my time in the industry. Indexes need to have effort, rigour and, yes, money invested into them. They should be created by professionals; and when it comes to cookbooks, you are essentially talking about a manual, and every manual requires a good index.

I learned a lot about many parts of the publishing practice from my friend and food writer,

. Her book Pepper was so meticulously researched and that information then so intelligently sieved and written onto page that I was crestfallen when it didn’t scoop at least one of that year’s most prestigious food writing prizes. I learned about the economy of how to write well when drawing on so much knowledge. I also learned a lot about book design – Christine once worked at Pentagram, one of the world’s great design studios. Her ‘change-one-thing’ suggestion radically improved my design thinking and those early draft layouts of Pepper. It remains one of the fundamental lessons that I apply to any new design project and the advice that I offer to many younger designers who I have worked with since. Back to indexes and I remember an hour spent on the phone with Christine hacking through the one we had proposed for her book. It was flawed and flabby and in need of pruning. Would people search for this term? Do we need to reference ‘Puy’, ‘pulses’ and ‘lentils’ or would just one of them be enough? She applied a rigorous reasoning to it all. The index was lithe, logical and supremely useful when we had finished.Edited well, and examined with care, an index should contain entries that enable you to re-locate a subject post-reading, but be equally seductive when one roams those subjects before they start. In non-fiction books, the index is a standard enough convention. Though it is unusual to see a work of fiction with an index, there are some famous examples. Tolkien allowed for one to be added to a later addition of The Lord of the Rings, to enable the proper naming of places, people and things, and to better guide the reader around his incredible make-believe world. Had it included an entry for ‘Gollum, death of’ then the indexer would be over-delivering on the brief, but failing their reader. In Georges Perec’s epic work of fiction, Life A User’s Manual, almost ten percent of its 600-plus pages is devoted to an index, the entries therein providing answers to riddles from the story itself.

A really good index can have the weight of a chapter in its own right, can be rich with narrative, and be buzzing with keywords and avenues to travel, and places to stop and ponder. A good index can function like an abridged biography of the book it supports.

If there is an obvious gap within the publishing tools of Substack then an indexing function might be it, because there is nothing quite like an index for scanning the breadth of a writer’s culture; those things which interest him or her. Contrarily, the smaller focus and niche of a writer’s world can have the magnifying glass thrown over it – whether to highlight the repeated mentions of a favourite artist or resource, cook or recipe. The broad and the narrow, the macro and the micro. To go to the Latin etymology of the word, ‘index’ comes from the index finger, the forefinger – that with which one points. I thought I’d point to such a world, by creating and updating with each new post a full hyperlinked index for A Thousand Fragments. I hope that it might provide a useful signpost to the other parts of my platform, perhaps paint a small biographical picture, or merely be an enjoyable place to spend some time, to roam and wander – a riverbed of a thousand glimmering subjects waiting to be discovered.

Chip butties

There is very little that was passed from my mother to her son by way of food knowledge or cooking inheritance. Less still from my father. He toasted bread over the fire on a thin wire fork and made sheets of glass toffee that we smashed into pieces with a hammer that lived on the pantry shelf. And he also cooked chips – really good ones. Dad would skin potatoes and cut each into slices, and then cut each of those slices into fingers. I’m remembering and repeating the process now; thin starchy ink is pooling onto the board as I chop and coating the knife in petal-like white blotches. He would place a quarter of a block of lard into the frying pan which would melt to liquid in seconds. And now, like then, there’s a colourless lake of melted lard in the pan before me. With a fish slice in one hand (and most probably a lit Benson & Hedges in the other) he’d push the pieces of potato around the boiling contents of the pan. I’d watch nervously. I still watch nervously. A few minutes, then flip and wait for the next side, and then flip again, and then flip again until all four sides were golden-brown. He’d spread margarine onto thick white Mother’s Pride. I have cheap thick white bread here and butter, but that will do fine. I fish the cooked chips from the fat and drop them onto a concertinaed sheet of kitchen towel. He trawls several chips onto the raft of the fish slice, taps the utensil carefully against the side of the pan to shake the fat from their long rectangular forms, and lifts them clear. He lowers them straight onto the bread. We arrange them uniformly, and quickly, so that the heat of the chips begins to burrow into the margarine. Into the butter. He inverts the salt cellar and shakes it over the top. I crush and sprinkle a few flakes of Maldon between my fingers and scatter the same area. He takes his glass bottle of ketchup and pelts the bottom and waits patiently for it to drop. I squeeze and zig-zag the plastic bottle of sauce from one corner of open sandwich to the other. On goes the top slice. The knife pushes down into the roof of the sandwich and through to the bottom. Half for him, half for me. Half for me, half for him. A culinary heritage. I would have been eight, maybe nine when last I watched him make his butty. I’d never thought to recreate it in the forty years since. Until now. It tastes wonderful.

Recommended other fragments…

Just read: La Femme de Gilles, Madeleine Bourdouxhe

I loved this book – a gift from a new friend. Elisa is married to Gilles and is utterly besotted. Her thoughts are consumed by him. The balance of her world is thrown off-kilter as Gilles’ attitude towards her begins to change. That world is then shattered on realising that the subject of her husband’s new infatuation is her sister, Victorine. So far, so typical a tale of love and infidelity. What’s incredible is the way in which Bourdouxhe writes Elisa’s mental anguish in such a gripping and nuanced way.

Now reading: Orwell’s Roses, Rebecca Solnit

I’m a huge fan of Solnit’s writing. She has the gift that only the very best essay writers have – to write about any subject with focus and pitch-perfect style, to engage you with her thesis, and to digress onto other subjects and absorb you in their affinities and contrasts, too. It’s not so much the direction or speed at which Solnit travels, it’s the joy and intelligence of her perambulation. Orwell was a keen gardener; he planted roses. With this, Solnit explores the writer and activist we know so much about through a sharp and original lens.

Podcast/Broadcast: Britain in 1974, The Rest Is History

Having lived through the faecal pantomime of the last five/ten/fifteen years of British politics, anyone below the age of fifty might be forgiven for thinking they’ve lived through an unprecedentedly bleak and despairing time. You should try 1974 for size: a year that saw two General Elections, British industry in decline, and the government paralysed in deadlock with the Trade Unions. Violence was spreading across Northern Ireland and the Yom Kippur War had sent oil prices sky-rocketing. Britain’s economy was in tatters and the ‘three-day week’ had been mandated on the people. Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook tell the bleak but brilliant story of it all over four episodes of their long-running podcast.

Music: Three, Fourtet

A new album from Kieren Hebden is usually cause for celebration. It almost always guarantees at least a few uplifting and completely absorbing tracks. Tracks that bubble and fizz, warm and soothe and, at their best, twist and develop unexpectedly and playfully. It’s almost always a clever blend of electronics and acoustics over the top of blissfully ambient soundscapes. Three has all of the above. Most wonderfully of all, it brought to mind and made me want to go back to listen again to his joyfully creative 2003 opus, Rounds. That album and this one are connected by the same shuffling backbeats and clever sequencing – a soothing electronic-acoustic blend with top notes of real joy and deep melancholy.

People: Paul Auster

It was with great sadness that I learned of the death of Paul Auster last week. A friend recommended his books to me when I was about twenty (thanks, Adam!). Back then, I was the perfect sponge for his style of writing and his type of storytelling. ‘An American writer with a European sensibility’ has been re-quoted so many times that I really have no idea who said it first, but it sums him up well. Fascinating tales and moments from his own life would often become the setting-off points for his stories. Many of his books centred around magic and suspense. They would be multi-layered mysteries, mysteries within mysteries, sometimes an author writing about an author, a book within a book. Leviathan, The New York Trilogy, The Book of Illusions… all brilliant books, but it will be to his memoir, The Invention of Solitude that I return first. This interview with Auster includes his thoughts on writing and a recounting of one of those amazing chance happenings from his life around which he was able to weave stories like no other.

Forthcoming events…

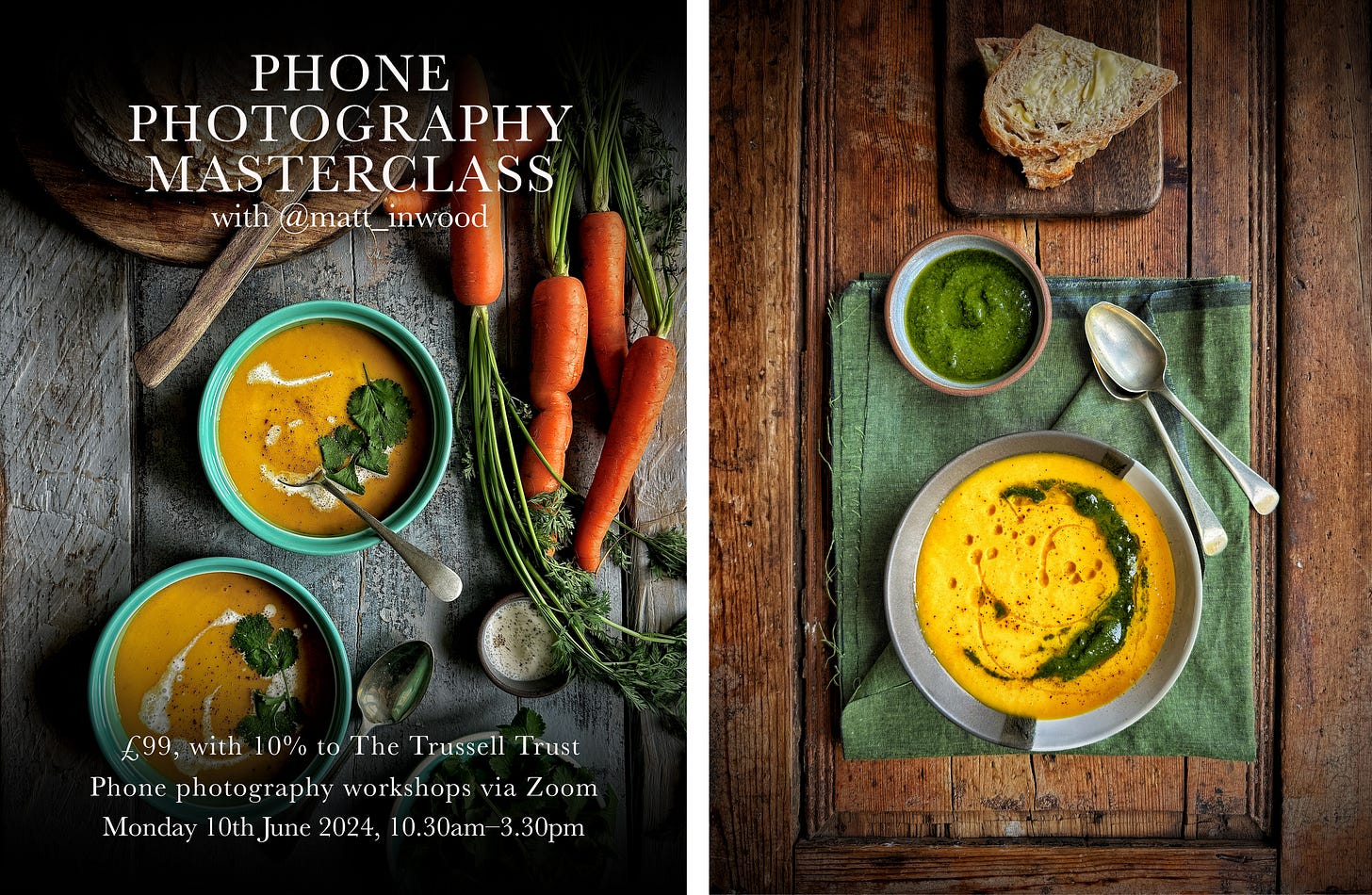

Phone Photography Masterclass

My next Zoom-based phone photography workshop date will be on Monday 10th June 2024. Find out all you need to know and book your place here.

The Writing Process with Mark Diacono

On Wednesday 15th May at 6pm, I’ll be talking with the food and gardening writer and Substacker extraordinaire,

, taking part in one of his online ‘Gatherings’, aiming to better inform those embarking on or engaged with ‘The Writing Process’. We’ll be talking about the way that we tell and share our stories, via both the written word and the images that we publish, and how all of that comes together on a social platform such as this. Some tips, some thoughts and a conversation with one of the most inspiring creatives using Substack today. You need to be a paid subscriber to to access the conversation, but if you do, you’ll discover that Mark’s is one of the most generous and good-value publications available on the platform.Note of nomencalture: ‘shard’ is of glass; ‘sherd’ is of pottery.

Mark’s book arrived on my desk a month ago and we’ve reviewed it in July issue of Homes & Antiques (out next month). It’s such a beautiful creation - both the physical object and the wonderful stories. We all loved it, especially my colleague, Jenny, a keen mudlarker and collector of sherds.

This is wonderful. Already a strong candidate for ‘Most Gorgeous Post of the Week’. Love it.