Double lives

I had been toying with the idea of the double as a leitmotif for an essay since a repeat viewing of one of my favourite films last month. In verb form, to double is to make one thing become two. In its noun form, that one object co-exists with a second identical object. I enjoy the creative possibilities that arise from these two simple definitions.

At the very end of last year, I moved old books on to new shelves and rediscovered a few pages of José Saramago’s dark and brilliant novel, The Double, the first of many fine books of his that I would go on to read (Blindness perhaps being his best). I found once again Dostoevsky’s equally dark book of the same name during that same move. This last week, I have spoken several times with my own ‘double’, my twin brother (albeit a non-identical one). And spoken too with my mother, herself a twin. On one of those days she called once, then twice, and then three and four times: a conversation that repeated, which doubled and then doubled again. Just a few days ago, whilst reading, I came across the adjectival form of a beloved proper noun for the first time – ‘Carravagesque’ – and then just an hour later, I heard its double, a reiteration, casually mentioned in a podcast, dropped into conversation as though part of a common lexicon I’d been ignorant of for years.

Half a life ago, while waiting to order a drink before a West End performance of Krapp’s Last Tape, I came face to face with my own double, my doppelgänger, and it was truly one of the most unnerving experiences I’d ever had… most profoundly because my mirror, my spit, my exact likeness seemed not to recognise himself in me. He was unable to distinguish what I had assumed to be indistinguishable, and I had to bury my horror as he took my order. I could go on, but I’m already several digressions into an essay that has barely set out its opening statement.

During the holiday, I watched The Double Life of Véronique (1991) with my daughter. It was a first time of watching for Tilly; a fourth maybe a fifth for me. There is something new to savour with each repeat viewing and, as so often with Kieślowski’s features, always something which resonates deeper with each subsequent watch. The film tells the story of Weronika and Véronique, two young women living in Poland and France respectively. Their likeness extends beyond name: they are physically almost identical, both very young, singers, each exploring and feeling their way around the world. Weronika has a heart condition which she succumbs to, mid-concerto, collapsing to the floor, dead. Across Europe, as though connected, Véronique feels the pain in her own chest, translated to her in that confusing moment as a sudden and profound grief. Sensing an imminent danger, Véronique calls time on her own singing aspirations the following day. Kieślowski places thread after linking thread into the film, objects and motifs which appear in both of their worlds (a shoelace becomes the most beautiful metaphor for what lies beyond the surface). Véronique consistently feels that she is connected to something, to someone whom she is never able to name or understand, but who she feels intensely. Towards the end of the film, Véronique’s lover discovers a photo of Weronika, captured unwittingly by Véronique when she was a tourist in Kraków a year or so earlier, and she sees for the first time the other life that she has forever ‘felt’. The film is beautifully elusive (Kieślowski was never interested in finding conclusions in his work), forcing us to consider what choices we might have made, what lives we might have lived, how closely connected we all are, and how delicate the line between life and death can be.

After making Véronique, Kieślowski went on to create his masterful Three Colours trilogy. Then, at the absolute height of his powers, he retired from film making altogether. Two years later he died and cinema lost one of its true greats.

‘There are too many things in the world which divide people, such as religion, politics, history, and nationalism. If culture is capable of anything, then it is finding that which unites us all. And there are so many things which unite people. It doesn’t matter who you are or who I am, if your tooth aches or mine, it’s still the same pain. Feelings are what link people together, because the word ‘love’ has the same meaning for everybody. Or ‘fear’, or ‘suffering’. We all fear the same way and the same things. And we all love in the same way. That’s why I talk about these things, because in all other things I immediately find division.’

Kieślowski, in an interview with Oxford University, 1995

‘If your tooth aches or mine, it’s still the same pain.’ How well we would do to recognise how closely we resemble and connect to one another; how vital that we hold up these mirrors more often.

Whilst writing this, I’ve been loop-listening to the beautiful music which Zbigniew Preisner composed for the film (Preisner’s music is almost always the main supporting actor in every Kieślowski film). The sensitivity and skill with which Kieślowski connects his viewers to what, how and why his characters feel is explained nowhere better than this short directing masterclass which details the importance of finding the right sugar cube.

Suffer together

I finished last month’s newsletter with a footnote on the origins of the word ‘nostalgia’. The etymology of words is important, not least because when we lose sight of those origins I think we lose the connecting threads to what we are trying to say and a value for what words actually mean. Words such as ‘compassion’. I listened to this word being spoken over and over again in a day of discourse around refugee boat crossings. Compassion is broken down into the Latin roots passio (suffer) and com (together). We suffer together. Compassion is not just a wish to improve the lives of others, to raise someone up. This is important because I feel it’s the point at which people can depart from and be done with well meaning and good intention. If we can’t lift others up without the risk of detriment to our own welfare or wealth then while we might be full and generous in our sympathy, it will not be the same as having compassion. Compassion requires that we must be prepared to suffer together; we must accept possible fear and hardship and work in our efforts towards good, not merely have hope or simply point in that direction.

Bourbon creams

Lunch would most often be a packet of a dozen bourbon biscuits or strawberry creams, shared with my brother: the most fat and sugar that twenty or so pence could buy. When there was a little more money, we would buy a packet each, although twelve sickly-sweet biscuits were more than even the most sugar-happy child would wish to consume. The best school days were the ones when there was enough food to cure our appetites, when we’d walk a few doors further on from the newsagent’s, to where most of our friends were waiting to buy their lunch. We’d queue with them and emerge ten minutes later with a cone of steaming hot chips, high on the glorious sting of heated salt and vinegar in our nostrils. A meal to eat. Sometimes there wasn’t any money for lunch and on days when that was the case we might play truant. Sometimes we did so with Mum’s permission, sometimes without; sometimes with Mum’s knowledge, sometimes with Mum in and out of sleep in her room, upstairs, from morning until night.

Over the years that followed, biscuits would become my only real ‘vice’. It’s rare that I am able to enjoy just one or two with a mug of tea. I take four or five or six and I aim to satisfy the slightest hint of hunger. That brother I once shared biscuits with, my non-identical double, will still do the same, too. A habit that was formed when we were children because biscuits were a meal, not a treat.

Thirty years ago we survived poverty, we survived my mother’s mental illness and we survived eviction from our home because of a welfare system that just about held us all together.

Today, more than 4 million children live in poverty in a country that boasts one of the world’s wealthiest economies. More families in this country are going hungry today than during the first weeks of Covid lockdown. In the year 2000, The Trussell Trust opened its very first food bank. Two decades later, there are more than 1,400 Trussell-Trust-registered food banks in the UK and almost as many independent ones in operation, many of which are struggling to stay open as demand increases and energy bills soar.

Recommended other fragments…

Just read: On Writers and Writing, Margaret Atwood

An interesting look at the various roles of the writer and the traditions, functions and myths of writing over the centuries. More erudition for me than inspiration; more theoretical than practical writing advice.

Now reading: Still Life, Sarah Winman

Beautifully written, character- and atmosphere-rich story that begins in Italy as the War is coming to an end. I’m just over halfway through and have been looking for every excuse possible to ignore work and family and to delay the dog walk by another half-hour for each of the days it’s been on the coffee table.

Podcast: Chip Kidd, interview with Debbie Millman on Design Matters

Kidd’s been responsible for some of the most iconic book covers of the last few decades, including Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park with ‘that’ silhouetted dinosaur. It’s an old podcast which takes in ‘Go’, his guidebook to design for children, his fear at delivering one of the best TED Talks I’ve ever seen (do go and watch it), his love of Batman, and his graphic interpretation of Neil Gaiman’s brilliant and inspirational commencement speech, ‘Make Good Art’, which every creative should watch immediately and start acting upon as soon as they’ve finished watching.

Music: Blackstar, David Bowie

Last week saw the seventh anniversary of Bowie’s death. Two days prior, on his 69th birthday, his final studio album was released. The timing of it all was part of what made the album so very powerful in those early months of listening. It’s become by far my favourite Bowie release. As a song to end both an album and a life, ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ remains one of the most haunting tracks I think I’ve ever listened to.

People: Misan Harriman

I’ve been an admirer of Misan’s stunning portraiture since I had the pleasure of meeting him, very briefly, a few years ago. Recent posts such as this one resonate loudly around the idea of compassion I was writing about above: putting in the work to lift others up.

Forthcoming events…

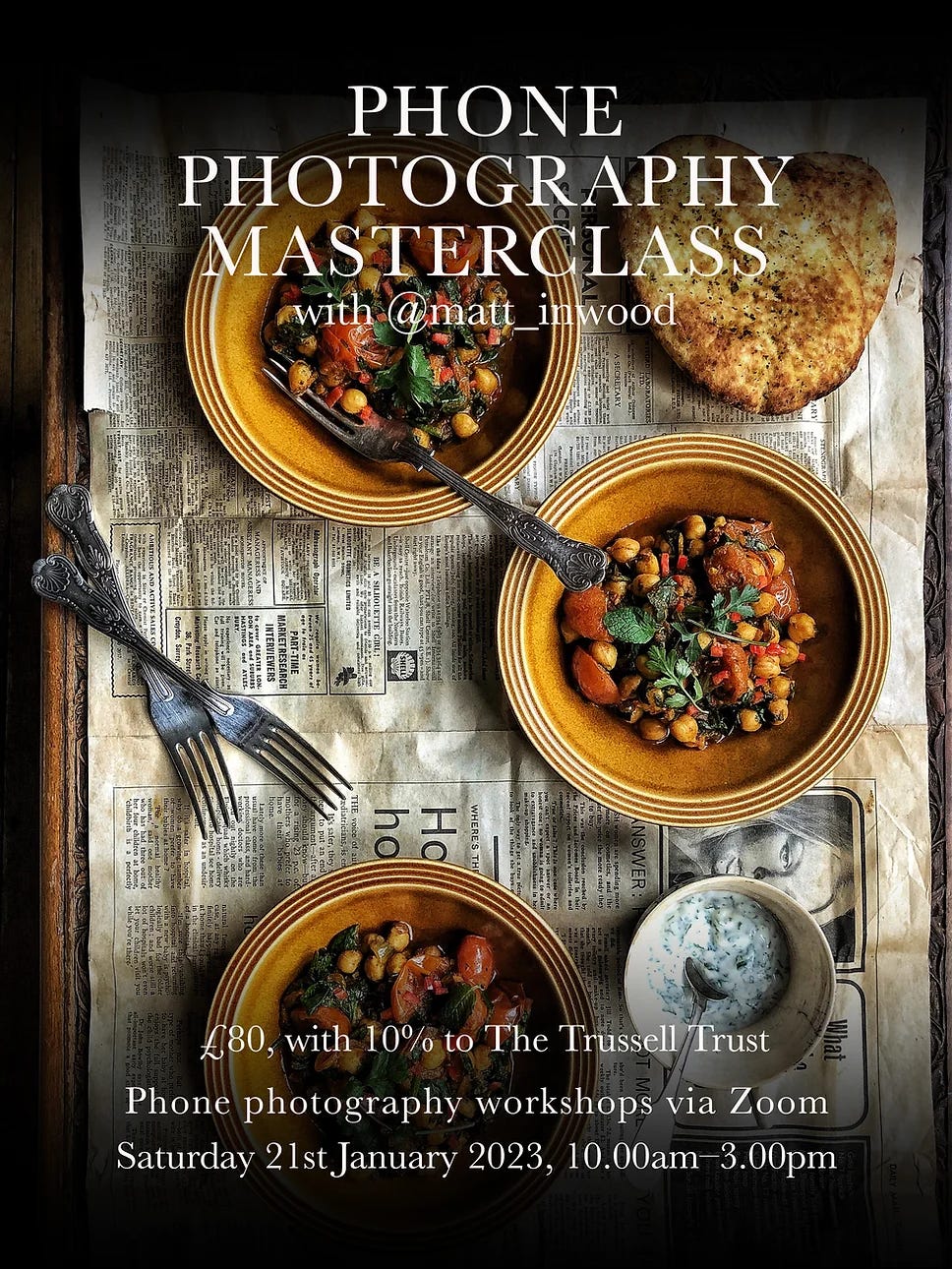

Phone photography masterclass, Saturday 21st January

Join me, via Zoom, for the first phone photography workshop of 2023. If you’re keen to improve your photographic and styling skills, either for personal or business development, then the workshop is an effective way to start. More than 1,200 people have participated over the last few years, with 10% of each £80 booking fee now donated to The Trussell Trust (over £2,000 since these donations began). Follow this link for more info on what the course entails. Free places are available each workshop for those who cannot afford to pay – simply drop me an email or message on Instagram if that’s you.

From next month, I aim to create a separate spin-off of this newsletter for those looking to get more from their phone photography. A fortnightly edition exclusively built around tips, advice, inspiration and practical guides for food photography. This will become a subscription newsletter. I’d love to hear from people interested in such a newsletter and know what you might like to see. You can reply to this email, comment online below this newsletter, or message me on Instagram to have your say.

I’m also reading Still Life right now. So far, I’m only several pages in, but I love Sarah Winman’s work and I can’t wait to see where this story takes me.

There was a time when I was obsessed by Kieslowski movies. It’s been a few years since I’d thought about them. Thank you for ‘bringing them back’ to me. I should rewatch them in the upcoming week. Your writing’s so beautiful.