Failing to write and read, a smudge of colour, forty-nine-year-old scallops

#11 | August 2025

Failing to write and read

It’s been a long time since I wrote one of these collections – 389 days to be precise. This was the format I began posting to Substack with, back in November 2022. They appeared monthly thereafter and then more sporadically, and then my attention turned to smaller single-subject pieces. I started to fail to write these ‘through’ the month, slipped from adding bits here and there – probably the death knell for most kinds of compendium writing – and they then became too big a thing to write from scratch a day or two before each self-imposed deadline. And so they stopped. But I missed creating them and so here we are: Number 11.

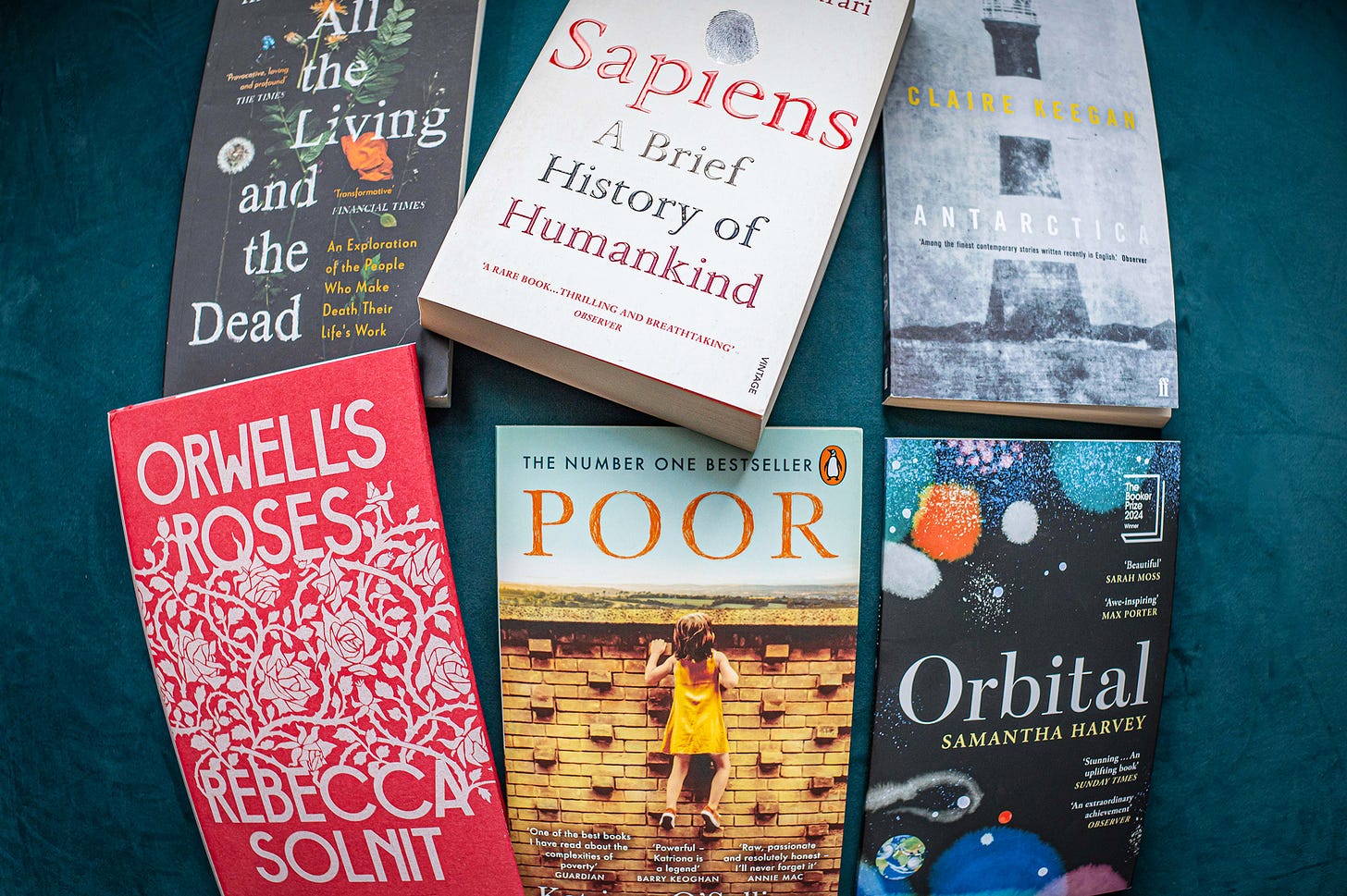

At the same time that this larger publishing format fell into decline, so too did my desire to read. Life is rarely straight-forward or straight in direction and took turns that made both of these creative pursuits feel incredibly difficult. I plugged away here and there, but, for various reasons, time spent reading brought with it an anxiety that there were more pressing things to be done. Reading or the thought of it has at times felt suffocating (not least trying to keep up with the relatively small number of friends and creatives I follow here). Nevertheless, I managed to read some very good books, and maybe a couple of great ones. The best was the one I had delayed reading the longest (no surprise it was also the biggest): Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens. It is a quite staggering achievement. Harari stands on the shoulders of many for the huge amount of research this book comprises, but while the information contained within is impressive, it’s the way in which he tells the story of how humans have evolved and what we have evolved into that makes it such a thoroughly engrossing read. A few other notable, occasionally stubborn reads from the last twelve months or so:

Alice Kaplan and Laura Marris, States Of Plague • Yanis Varoufakis, Technofeudalism • Hannah Richell, The Search Party • Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens • Juhani Pallasmaa, Eyes Of The Skin • John Berger, The Foot Of Clive • Samuel Beckett, Company Etc • Madeleine Bourdouxhe, La Femme De Gilles • Rebecca Solnit, Orwell’s Roses • Paul Auster, The Red Notebook • Gwendoline Riley, My Phantoms • John Berger, Confabulations • Brian Dillion, Affinities • Garth Greenwell, Cleanness • Emanuele Coccia, Philosophy Of The Home • Deborah Orr, Motherwell • Albert Camus, The Fall (re-read) • Katriona O’Sullivan, Poor • Samuel Beckett, First Love & Other Novellas • Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, Abundance • Samantha Harvey, Orbital • Leszek Kolakowski, Freedom, Fame, Lying & Betrayal (re-read) • Claire Keegan, Antartica • Hayley Campbell, All The Living and the Dead

A smudge of colour

Last September, my youngest daughter started Year 10 at school, the year when ‘grades start to count’ and ‘effort will get you the reward you deserve’. Parental platitudes back then, almost unintentionally, were ratcheted up a notch or two in seriousness; each like a short, sharp snip through the cord of soft, huggable childhood every time that we repeated them. Choosing subjects from which to form a path into vocation and adulthood can feel like something that is done to you. The school will advise, the curriculum will narrow and restrict, the parent will nudge, and the student will choose: certain of some options, worrying over others, perhaps floundering over all. In the end, it can feel like a tail being pinned onto a donkey of education. Ever since, we have been trying to steer and limit the anxieties of the ensuing ride.

Most of her choices feel like they have been the right ones for her. Of all those that she did choose, art is the subject that she is showing the most aptitude for. She has the same natural talent of her sister, the same creative flair of her mum, and seems to share the same love of faithfully representing parts of this world that her father did at her age. It was a sentimental moment to buy for her a first set of artists’ pencils, from the softest grades of 12 and 10B through to the hard, fine points of 2 and 4H – I cherished the set that I had as a child. And then there was the joy of seeing an old box of chalk pastels out on the table once again – never a medium I excelled in. They were too beautiful in form and colour – snapped and stubbed sticks of pigment that only the artist can truly revel in the heft of – not to photograph; too vivid in associated memory not to fix and hold onto for longer.

Forty-nine-year-old scallops

At the start of July I met with my twin brother, Pete, to walk a day around the streets and parklands of our old childhood haunts in Birmingham. The excuse was a birthday that would fall a few weeks later at the end of the month, by which date we would have shared in a century of life together. This was a chance – the first in a couple of decades – to revisit a time and the feelings of when we were inseparable and the clichéd truth of life being much, much simpler.

We walked with a notion but no strict plan of where to go next, nor a well-formed idea of where or when we would finish, but seven or so hours later, we’d pretty much checked off every significant place in or along which we had spent our youth. We finished with dinner at the public house where we enjoyed our first legal drink (and several previous illegal ones). We talked almost exclusively about our childhood as we walked: it was all before and around us, close, tangible. One thing that we both observed is that the scale of everything is so unsettlingly different when seen and walked as an adult. We started from the top of the road of our first childhood home, baffled as to how we had arrived at No.48 so very quickly when it seemed to take an age to get from one end of the road to the other as children. The grass lozenge where we used to set down jumpers to kick around a football as kids could be counted out in just a few forty-nine-year-old’s steps. The dangerously steep banks of the grass-lined dells we would slide down for hours as children were little more than mild gradients, scaleable in a few impatient strides today.

In the middle of the day, we stopped for a quick snack at Clay Lane Fish Bar, the chippy from our childhood. The cheapest item on the menu back then appeared to be the cheapest item on the menu today: the potato scallop, listed simply, rightfully, as ‘scallop’. It was the thing both of us were craving. The scallop is a chip shop delicacy which I was shocked to discover was not a universal delicacy when I moved to Bath, away from Birmingham, when I was eighteen years old. It occurred to me that the last time I had bought one it would probably have set me back some ten or twelve pence. Pete did the honours this time, spending a pound apiece. We sat in the bus shelter outside what used to be Sam’s newsagents on Woodcock Lane – the place where we handed over weeks’ worth of pocket money for Panini stickers, Eagle comics and Shoot magazines, and shamefully occasionally kept watch as our friends stole various of the aforementioned. The scallop is a slice of potato, coated in batter and deep-fried. It should be served hot, showered lightly in salt and doused heavily in vinegar. If your nostrils don’t flare as you raise it to your mouth, you should add more vinegar. The crisp batter should be starting to soften from the heat and the acid as you eat; the potato should be cooked, but not too soft. Reader, that scallop was wonderful: faithful to the cherished memory of that previous one some thirty-plus years ago.

The scallop, much like the glimpse down the alley and over the back gate at Bosworth Road; much like the bedroom bay window we pointed to that used to display the Star Wars AT-AT walker at Mark Wooton’s house; just like the still-running stream that we would jump back and forth across at Jubilee Park; like Aunty Doll’s house with the outside loo which backed onto the canal; like the bridge where the bus got stuck in the snow one winter; like the sycamore tree that used to helicopter down its seeds outside our bedroom window every autumn: each returned our childhood to us for seven or eight warm, blissful hours. The most wonderful of days with my four-year-old, ten-year-old, eighteen-year-old, forty-nine-year-old best friend.

Recommended other fragments…

Just read: Letters To My Grandchildren, Tony Benn

“I have divided politicians into two categories: the Signposts and the Weathercocks. The Signpost says: ‘This is the way we should go.’ And you don’t have to follow them, but if you come back in ten years’ time the Signpost is still there. The Weathercock hasn’t got an opinion until they’ve looked at the polls, talked to the focus groups, discussed it with the spin doctors. And I’ve no time for Weathercocks, I’m a Signpost man.” Benn wrote this book for the generation to come, aware of all the tradition and the great history in which his own generation was still connected to. One of the most principled politicians of that and any generation, Benn is the signpost that many on the left still look to on matters of moral, ethical and political difficulty and still try to emulate in terms of clarity and conviction.

Now reading: Small Island, Andrea Levy

I’ve not read any of Levy’s work prior to this, though this has been sat on my shelf for about four or five years. She’s a consummate writer and this is an incredibly well crafted novel. It deals with themes of war and Empire, love and extreme prejudice and does so through the interweaving first-person stories of its four main characters. Gilbert is Jamaican and joined the RAF to help the British forces in their fight against Hitler. He decides to stay in England, but converting to civilian life reveals the same racism, bias and hostility that he experienced as an officer, fighting for a country that wasn’t his own. He ends up in Earls Court, into the boarding house of Queenie – the glue of the novel – whose own husband, Bernard, also signed up to fight in the forces, but who has not returned following the war’s end. Gilbert’s wife, Hortense, has dreams of England more fanciful and delusional than her husband. She is brought crashing down to reality when she arrives in London. And when Bernard does eventually return, years later to Queenie with his father’s house now full of Jamaican lodgers, the attitudes and ingratitude of this small island are brought sharply into focus.

Podcast: The Diary of a CEO, Mo Gawdat on AI:

A disclaimer: not withstanding the troubling rise of health ‘claims’ made, shared or hosted on this podcast, I’ve always disliked the pomposity of the title and find the format of Bartlett’s series a little too long-winded and flabby – self-important; an eavesdrop into one man’s journey of self-improvement. This episode with Mo Gawdat, however, felt like it might be essential listening. Gawdat – like his host, a very wealthy man and prolific podcaster – has had an interesting life and shares warmth and vulnerability alongside his insights. His thoughts on artificial intelligence were informed and fascinating when I read them a few years back in his book, Scary Smart. His updated thesis paints a far more dark picture than his writing of 2021. If you’re of a nervous disposition about our future alongside the growth of artificial intelligence, you might wish to avoid.

Music: Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You, Ethel Cain

One of the things I like about Ethel Cain is that I really don’t like all that she does. She does her own thing and seems to cater not to her fans, and certainly not to the critics, but also not to the times. She is a quite brilliant writer of lyrics and an equally gifted creator of richly emotive music. Her subject matter is often dark – the narrative arc behind her sonorous debut, Preacher’s Daughter, makes for a disturbing close listen. Her musical tastes cross and merge between pop, goth, gospel and rock. The ’80s synths of ‘Fuck Me Eyes’, the second single release from this new album, are infectiously catchy and headily nostalgic; it’s easily my favourite song of the year so far, but the rest of the album is beautiful in very different, but similarly intense ways.

Watch: Shifty, Adam Curtis

‘When power begins to shift in society, everything becomes unstable, exciting and frightening.’ Curtis’ films show us how individualism and atomisation have been two of the most prevailing and troubling forces of the Western world over the last four or five decades – eroding the realities that we had previously understood to be shared and agreed upon. Shifty begins with the arrival of Thatcher into power. It ends with Blair and Brown at the helm. The viewer is left to consider what has really changed between and indeed since these two eras, because power was and continues to be ceded from the State to the corporations through both periods of governance and subsequent ones since. The film finishes with the building of the Millennium Dome, a project which he concludes confirmed one incredibly alarming truth: that the Liberal elite that had been running the country for over 150 years no longer had anything to inspire with regarding the future of Britain. The Dome stands tall as a metaphor for the decline of British political power that Curtis paints so provocatively across these compelling five episodes.

Forthcoming events…

My next Zoom-based phone photography workshop date will be Monday 22nd September 2025. If you’re a subscriber to this newsletter, you can claim 20% off the price. Find out all you need to know and book your place here.

Loved this Matt, thank you - and AMEN to Tony Benn. Can we have a few more people of principled conviction in public life please

Wonderful to see this format return, Matt … so much to glean from it - your ‘not much reading’ strikes me as plenty amidst the writing, birthday celebrations, parenting, dealing with life’s rollercoaster, being a lovely friend, and all …

Many trails of breadcrumbs to follow.