First sentences

The subject of an opening sentence seemed as good a place to form and begin a newsletter as any. In one of the many open browser tabs that weigh so heavily on the conscience of someone who suffers from an overwhelm of web pages he can’t ever quite close, was an article I read and enjoyed several months ago. It concerned one of the most famous opening sentences of 20th-century literature, from Albert Camus’ The Outsider (L’Étranger). For those who have read and enjoyed the book, it’s very likely you will remember it, such is its arresting bluntness: ‘Mother died today.’ In the original French, that sentence reads, ‘Aujourd’hui, maman est morte.’ The complexities of the translator’s art have long fascinated me, not least because most of my favourite authors write in languages other than English. Bloom, a translator himself and a scholar of Camus, believes that most important first line of arguably Camus’ most important and first book has been badly translated by all since it was first published in English, back in 1946. Subsequent translators would repeat the mistake, until the publication of Matthew Ward’s translation in 1988, who switched the word ‘Mother’ for ‘Maman’. This softer variant on the word is important. One is harsh and cold, the other is warm and softer. For a book in which so much evolves from and depends on the protagonist’s relationship with his mother, it seems incredible that one word could perhaps lead us to set off and run with a completely different idea of his character’s inner mind than that which Camus intended. Bloom also believes that opening sentence should lead, not finish, with the word ‘today’, emphasising the interruption of the present ‘now’ in which his character lived so unrepentantly.

I’ve started re-reading all of Camus’ work just as my daughter has begun studying The Outsider for A-level English. I am taking much real and vicarious pleasure from scanning the Post-It Note tabs and scribbled marginalia that plaster her Penguin Classics edition. Bloom’s insightful essay is one against which she’ll now be able to weigh her own initial thoughts about the first book of her father’s favourite author.

Read ‘Lost in Translation: What the First Line of “The Stranger” Should Be’ by Ryan Bloom

Blossoms

From Bloom to blossoms…

My older brother is a huge Doctor Who fan. Subjected by him to many childhood hours of recorded playback on the family VHS video player, it was inevitable that his brothers, twins Peter and Matthew, would develop a soft spot for the BBC’s flagship sci-fi programme, too. Since the series’ impressive revival in 2005, however, I could probably count on one hand the number of stories I’ve actively sat down to watch. The exception comes around every few years though, with one particular episode that I tune in for without fail: the Doctor’s regeneration. Indeed, my earliest memory of watching the show dates back to a Saturday afternoon in March of 1981 when Tom Baker fell to his ‘death’ from a satellite tower and transformed magically into Peter Davison (‘my doctor’). Regeneration time came around again last month with a final fling for thirteenth incarnation, Jodie Whittaker. [SPOILER ALERT] As the story reached its end, the Doctor, resigned to her fate, parked her TARDIS on the limestone roof of Durdle Door. She walked out to take in one last sunset, sniffed the air and declared, ‘the blossomiest blossom’. The blossomiest blossom. I wish to linger on those words, but to digress, away from fictional travels in time and to turn instead towards the very essence of how we use that time and to the origins of that most charming expression.

In 1994, Dennis Potter, one of Britain’s most acclaimed dramatic writers, was dying of cancer. With just weeks, maybe months to live, Potter granted an interview to Melvyn Bragg and spoke for forty-five minutes about his life and moreover his living in the knowledge that one day soon Rupert would finally finish him off (Potter had named his cancer after media proprietor, Rupert Murdoch). There are so many moving moments throughout their conversation (a monologue, really), but none more so than his explanation of living in the moment. His terminal diagnosis had given him a super-heightened awareness of the ‘nowness’ of life. He describes working at his desk and observing the blossom of the plum tree growing outside, underneath the window: ‘It is the whitest, frothiest, blossomest blossom that there ever could be. And I can see it. Things are both more trivial than they ever were and more important than they ever were. And the difference between the trivial and the important doesn’t seem to matter, but the nowness of everything is absolutely wondrous.’

Potter describes the beauty of something not made glorious in anticipation or relished in recall, but simply savoured as it is, tethered to the most precious present.

The rest of their conversation yields so much more. On the anxiety of losing a favoured pen in childhood: ‘the pen-ness of that pen and the lost-ness of that loss.’ On the idea of believing in God: ‘religion to me has always been the wound, not the bandage’. Potter, for me, much like his contemporary Derek Jarman, was someone whose written or spoken words touched me far more than any of the dramatic works they created for TV and film. I hope that doesn’t sound too disrespectful, but I’d urge anyone to read the moving last journals of Jarman, and to spend just shy of an hour with the beautiful final thoughts of Dennis Potter, below.

Watch ‘Seeing The Blossom’, Dennis Potter’s last recorded interview with Melvyn Bragg

Echoes

Proof that I do occasionally commit to closing browser tabs is that I can’t recall whose tweet it was last month that spelt out so well the particular malady of the echo chamber. Such is the power of social media algorithms that the breadth of news and opinion we consume is forever likely to be weighted heavily towards the thoughts of those who wear the same scarves as us. Often, that includes referencing and defining ourselves against those who swing and swirl their opposing tribal scarves with the greatest vigour. These positions seem more deeply entrenched with each passing post or tweet, strengthening what we feel secure about and reinforcing what we feel frightened of, angered by and opposed to. With the world at touching distance from our fingertips, it feels as if this rapidly developed interconnectedness is just as likely to be reductive to our thinking as it might be expansive. It’s a refinement we seem addicted to, rewarded by every reverberating nod of another’s concurring head. It is easy to mistake a plurality of voices for a variety of opinion and ignore that it is but one singular hive we crawl and buzz around in.

Following the latest graceless and blundering intervention by the world’s wealthiest monolith, it seems that many of us are destined to soon re-evaluate our continued presence on one of these social platforms. For what it’s worth, I’d be sorry to see Twitter change in the ways mentioned and predicted, but I really don’t know that I’d have the heart or stomach to give my time, energy and hope to another such space.

The algorithm has been refined endlessly, not to bring us more of what we want and take us to new ideas and new places, but to bring us those same wants, repeated over and over again. We’re penned in, and it’s about to get worse. The strong iron walls of our chambers have been painted and brightly decorated for many years. The rust along the perimeter is now all too easy to see; the musky smell too strong to ignore.

My daughter’s egg yolks

Tilly used to love a fried egg. She was never able to eat the yellow bit though, only the white. It’s conceivable that I might have reserved the yellow and made custard or Hollandaise halfway through the week. Instead, I would cook the egg whole each time and then cookie-cutter out the middle. As she ate the white, I would eat my daughter’s egg yolk. I have a love-hate relationship with eggs (like many, I suspect) and too much contemplation of what I’m eating (indeed, even cooking) would be enough to put me off them altogether. I’m not sure I always wanted it and I’m fairly certain I didn’t always enjoy it, but we carried on this way for a couple of years – her with her hole, her half, in the middle of the thing she knew to be an egg; me with my middle, my half, of the egg I had cooked for her. Our shared meal.

I fried an egg last week and placed it on top of two courgette fritters – a simple dish to use up a few ingredients way past their best – and I remembered my daughter and the cutter once more. Food connects us to others and to our past more closely and more quickly than almost anything else. I used to make pancakes (more eggs) each and every Saturday for both of my daughters. It’s something they grew out of, but which I never did and never will – the urge to please them with these staples of our life and our love gets switched back on in the instant that such dishes are requested once more. When Bessie hesitantly asked me to make pancakes for her a couple of weekends ago, she calculated only for the time and labour it would involve, but was blissfully unaware of the way that it would reach for the heart of her father.

Memory has long been woven into food, and food into memory. Proust wrote about this more famously than most, but Bee Wilson did so a few years ago in a way that entwined science and love in one compelling read.

Recommended other fragments…

Just read: The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

I’m now three books into re-reading the full works of Camus. This philosophical essay presents a framework for the absurdist thought that underpins the first cycle of Camus’ work, including The Outsider.

Now reading: And Finally: Matters of Life and Death, Henry Marsh

I’d love for everyone to read Marsh. He writes beautifully on subjects that centre around his work as a brain surgeon, but which broaden out into all of life and, inevitably, death. With this third biographical book centring around the cancer which now foreshadows his own passing.

Podcast: Noel Fitzpatrick, interview on ‘Full Disclosure with James O’Brien’

An incredibly moving interview about striving to be the best kind of human you can be from a man best known for the heroic compassion he shows to the animals in his care.

Music: ‘Requiem pour le Père Kolbe’, Wojciech Kilar

You possibly know the final two and a half minutes of this piece of music from one of the last great films of the twentieth century. Wilar’s requiem scored an earlier film which told the story of Kolbe – the Polish priest who sacrificed his life in Auschwitz by swapping places with a fellow prisoner, condemned to death.

People: Feasts and Fables

JoJo (Feasts) and Barrie (Fables) celebrate the work of others. Their weekly newsletter is a trove of valuable links to that work, always eclectic, always something new, always striving to highlight projects and ideas which reflect the yellow hue of the creation, hope and positivity that runs through all that they themselves do and aspire towards. They are currently building Encouragement Farm in their own little corner of western France. They inspire quietly. I couldn’t finish this first newsletter without a mention for the two people chiefly responsible for inspiring my own. Do go and take a look.

Forthcoming events…

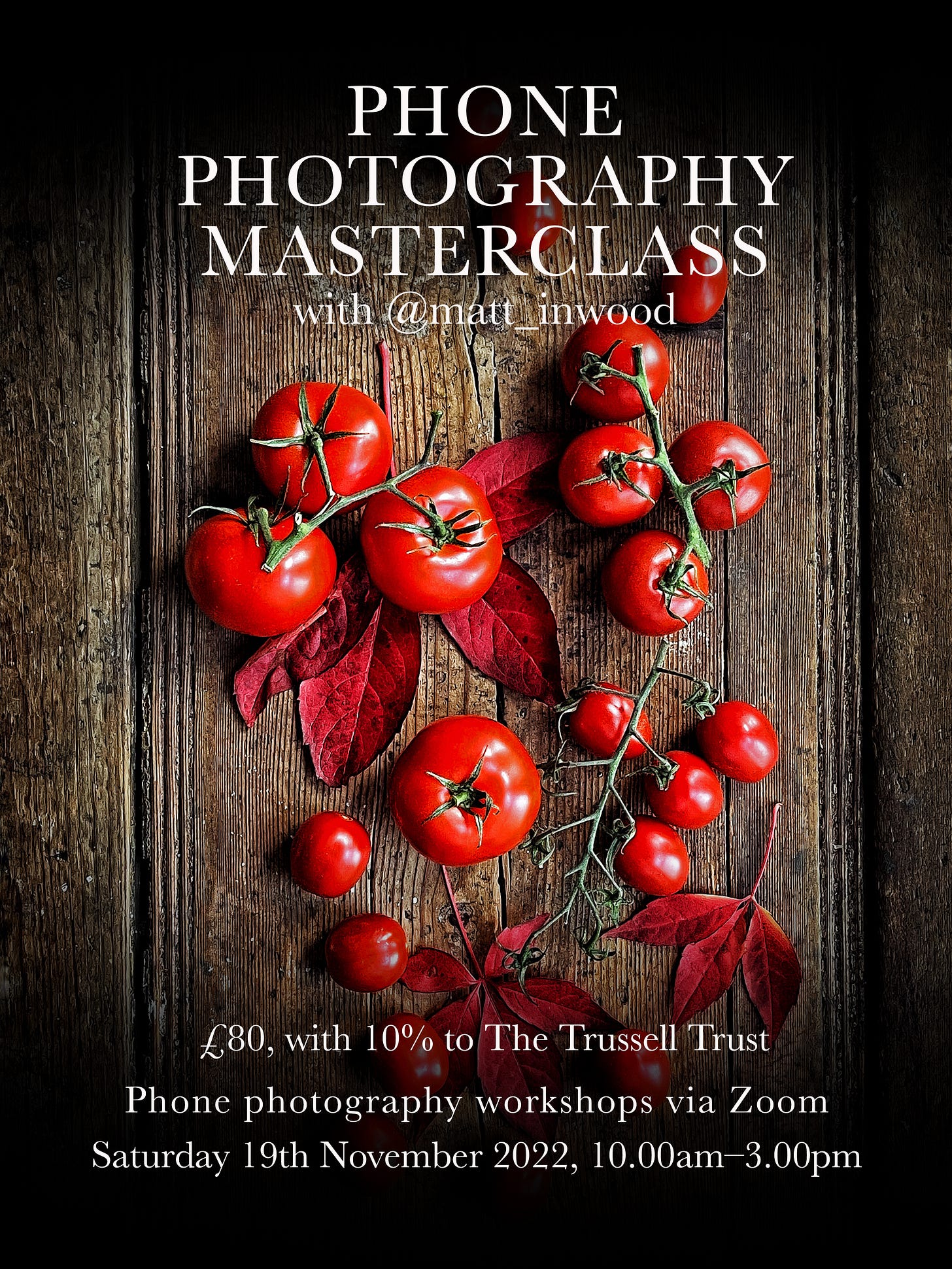

Phone photography masterclass, Saturday 19th November

Join me, via Zoom, for the penultimate phone photography workshop for this year. If you’re keen to improve your photographic and styling skills, either for personal or business development, then the workshop is an effective way to start. More than 1,000 people have participated over the last few years, with 10% of each £80 booking fee now donated to The Trussell Trust (over £2,000 since these donations began). Follow this link for more info on what the course entails. Free places are available each workshop to those who cannot afford to pay.

As luxurious and textured as I knew it would be. I was scratching my head to recall an article about Camus we'd shared in our musings a while back ... I found it in the School of Life:

https://www.theschooloflife.com/article/camus-and-the-plague/

A beautifully-written trail of breadcrumbs ... oh, and a spark of curiosity that has me poking around in Substack to see if there's a place for Encouragement Farm to share ideas and words.

Love it. Knew I would; so glad to see it emerge.

Bx

This has been a very fine start to my week. A lovely selection of pieces and I'm so glad that more of your writing will be winging its way to my in-box soon.