A finger and leaf (each lifted), the joy of unread books, pieces of toast

#2 | December 2022

A finger and leaf (each lifted)

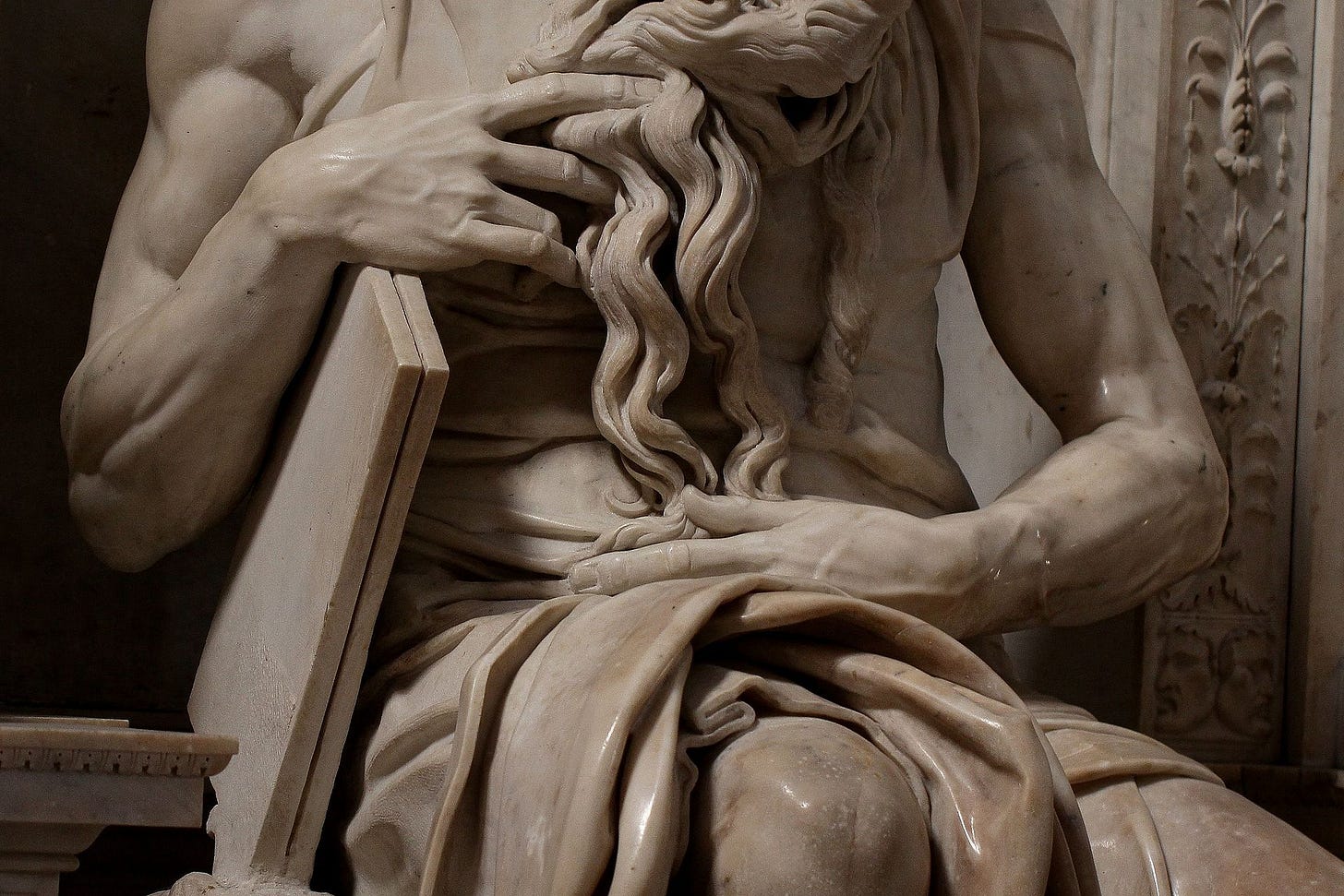

Michelangelo’s marble sculpture of Moses sits in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. It was one of the many statues that made up the design of the tomb ordered by Pope Julius II, in 1505. The Pope would die eight years later, three full decades before his tomb was finally completed, never to be interred beneath the stunning creation that he commissioned.

Moses is beautiful – the poise and perfect tension of each limb, the folds in the drapery, the soft billows of beard (hair being an almost impossible form to render in marble). His right arm is perched on the two stone tablets which bear the Commandments received from his Maker. Arguably though, the most exquisite detail can be found carved into Moses’ right forearm. There you will find the small muscle (extensor digiti minimi) which contracts only when the little finger is raised, which it is, interloping with the cascading curls of that beard. Moses is an incredible work of art: an immaculate testament to scrupulous study and observation. One can only imagine the expert eye required to see those individual characteristics; can only marvel at the time taken studying the connectedness of those elements, their size, their weight and their motion: a little finger, lifted.

In my photography workshops, I often tell my students that they should spend far more time looking at the fruit in front of them than staring at the camera screen on which that fruit appears. It’s a principle that was rammed into me way back in my art college days: that it should take only a few seconds to place a mark on the paper, but require ten or twenty seconds to look at and study each line, each shape and each show of light on the life model in front of you.

Such small and magical details are carved into the routine of each of our days. I noticed one of them during my walk this morning. The grass was sodden from last night’s rain and my feet were wet from boots that long ago ceased being waterproof. It was a repeat of the same walk and the same conditions that I’ve experienced almost every day these last few weeks. As I climbed the knoll that takes you up, away from the river, I caught sight of something alive and yellow, flickering in front of me. It spun perfectly, then bobbed – lifted – on the wind. I stopped still to stand and watch it dance; noticed the sienna, burning at its edges; felt the wind, elegantly shifting this relic of autumn up, across, then up and looping-down with unparalleled grace. It sailed through the air like this for nine or ten seconds, falling finally, golden and shimmering on the verdant floor. I picked it up and placed it carefully into my coat pocket. Once home, I sat it on the windowsill and just now noticed its dried form, curled over, perhaps exhausted from its earlier performance, but no less beautiful.

The joy of unread books

A few weeks ago, I sat down to lunch and a chat about shared passions with fellow designer Andrew Eberlin and we came onto the subject of books that one owns, but never gets around to reading. These are the books which we tend to amass over years, often bought with honourable (sometimes dishonourable) intentions, but that we never quite find the time or desire to read. Literature’s so-called ‘canon’ has much to answer for: a pressure on the reader who wishes to think themselves 'serious' and so vows to read Ulysses, Moby Dick and War and Peace, half-knowing that one or two years later, Joyce, Melville and Tolstoy will have been reviewed only by the quarterly visit of the feather duster. There are books that we buy for display, for shelf or coffee table; to telegraph an identity or intellect to those who might visit and glimpse an idea of our lives. There are the ones we buy to please and connect with others, because someone trusted or respected told us that those books were worthy of our time. There are the books that we desire most desperately to read one day and acquire the next, only for that flame of passion to be snuffed out by the end of the following week. There are the Venn diagram books that connect to something that we love, whereby Plath might beget Woolf, and lead to Hughes and Winterson, too: authors who open doors that lead us to dozens of new doorways. And there are the books that we receive as gifts which, though no doubt chosen with care, will inevitably be parked behind those that we have mentally queued for reading first. It is easy to feel shame about the books that sit unread on our shelves.

Above my desk sits an immaculate copy of Robert Musil’s one-thousand-one-hundred-and-thirty page ‘masterpiece’, The Man Without Qualities. I am willing to believe it truly is ‘a work of immeasurable importance’, but I suspect I may never find out. It will still be sat there, impeccably, next year: no hint of a crease upon its formidable spine, no single dog-eared corner to be found, not a trace of sebum which could DNA-link the edge of a solitary page to its seemingly profligate owner.

Yet books are not meant to be read straight away. Nor need we solemnly promise ourselves that we must read them at all. The books we have read are, in most cases, finished with – as likely to represent a multitude of autobiographical tombstones as they will a signpost for who we are now. If anything, it is those unread books on our shelves that still carry the exciting pulse of something new. ‘Every private library’, wrote Spanish philosopher José Gaos, ‘is a reading plan’. Unread books are not a collection of our cultural failures, but more a map of the places we have yet to travel towards. They are the towns and cities and countries and continents we have yet to discover, but also the rooms we might inhabit, the voices we’ve never before heard and the clothes into which we had no idea we could fit. They are the smell and flavour and feel of things foreign. They are the bridges that take you from foreign, on towards found and familiar.

In Patrick Süskind’s essay, ‘Amnesia in Litteris’, the author describes being unable to remember the reading of most of the books within his library. He consoles us with the idea that we should not worry about retaining words, characters, stories, but instead simply appreciate that we are changed by our reading, regardless of whether we might have forgotten the beginning before we have reached the end. And so it seems that even the books that we do read can so easily retain their unreadness and yet have imparted value.

If an awareness of unread books should sink you into anxiety, then a tour of the vast library of the philosopher and novelist Umberto Eco may well plunge you into despair. The Italian claimed that, ‘a private library is not an ego-boosting appendage, but a research tool.’ For Eco, ‘Read books are far less valuable than unread ones.’ Consolation then, that the book yet to be read is a book full of potential usefulness and possible joy. For me, I’ll take satisfaction from both the unread Robert Musil and my battered and beloved Albert Camus. And I’ll remain grateful for the books that I both can and can’t remember.

Watch Umberto Eco walk through his library

Pieces of toast

Memories of taste can be hoodwinked by time, place and various other swindles of the senses. The watermelon that quenches in dry, forty-degree Mediterranean heat will be savoured quite differently from the one spooned onto plate at the air-conditioned hotel breakfast buffet. Those separate wedges might have been hewn from the same fruit, but their tastes will be incomparable.

Several years ago, I woke in hospital one morning, painfully hungry. An intubation tube had been removed a day or so earlier; drugs, pain and lethargy dulling all of my senses. I was asked if I’d like to try some breakfast, ‘just a little toast, perhaps?’

Toast is the meal that has started many of the days of the forty-seven years of my life.1 When I was a child, Tuesday was benefits day, the day that Mum would draw money to buy what was needed for the next seven-day cycle. It sometimes didn't quite stretch and Sundays and Mondays could often turn out to be the most dismal of the week. Having bread in the house was a reasonable calendar indicator of how close we were to that next day of welfare support. It was also sometimes a barometer for the ravages of an illness that could see the needle of Mum’s depression swing from euphoric high to crumpled and bedridden for the next five or six days. We drew both happiness and despair from our poverty, but pleasure always from toasted white bread.

Back then, it would have been margarine spread instantly across hot toasted slices of white Mother’s Pride. It was downed with a mug of sweet tea, sugar enough to stand a spoon in, after Dad. One round of soft, greasy toast plus tea would follow another. It was wonderful. There were also the slices of toasted bread that came from the extendable metal fork which Dad would hold over the glowing embers of a coal fire. It’s one of only a few food experiences I can recall sharing with him and, again, it was wonderful. There were the tainted pieces of toast that had cooked in the eye-level grill above the hob, where a week or more’s accumulated cooking fats from cheap beef burgers and sausages still sat in the pan. There were the black, utterly carbonised toasts, forgotten by Mum, with grill-pan lakes of cooking fat sometimes alight underneath them when we discovered their fossilised remains. There were the occasional toasts or sandwiches of Monday evening, decorated with the salty elixir of Sunday’s roast beef dripping. Toast was a staple of childhood. Today, unless I am away from home, I still eat toast for breakfast, usually a granary slice with avocado or tomato scattered over the top. I’m quite sure I will do so for the rest of my days.

But, back to the beginning of this story, and the buttered white toast I received in hospital several years ago which was the best toast I’ve ever eaten. Cheap white bread, cheap butter, no doubt. Warm, but flaccid; browned, but glowing yellow in its centre. A mug of hot sugary tea alongside. Four halves of bread on the plate, followed swiftly, thanks to the kindness of the carer looking after me, by four more. It was the cheap white toast of childhood. It was the savouring of food when one has been deprived of food. It was both the flavour of coal smoke and not; both the spoil of grill pan burger fat and not; it bore the puncture marks of Dad’s toasting fork and yet did not. It was the primal overpowering joy of food and food memory.

Recommended other fragments…

Just read: The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit

Solnit’s research always seems so impeccably thorough. Her writing weaves delicately wistful narratives, often beginning with just one object or subject (an apricot, her mother’s Alzheimers disease), but touching on so much of the world that surrounds them. She lives inside her stories and yet seems able to stand omnisciently outside of them, too.

Now reading: A Man’s Place, Annie Ernaux

As with Solnit, above, I discovered Ernaux's work only recently (helped no end by the beautiful translated books that Fitzcarraldo Editions produce). This book is the story of her father, ‘a hard, practical man who showed his family little affection’ told in Ernaux’s brilliantly frank, spare style.

Podcast: Richard E. Grant, Desert Island Discs

Some great musical choices and a fascinating life story, but it is that his life has collided with and been entangled by grief that hits so beautifully hard in this episode.

Music: ‘Pistol’, Cigarettes After Sex

Ethereal vocals paired with haunting guitar pedals and reverb means I’ve always had an awfully-soft soft spot for this three-piece dream pop band from El Paso, Texas. So blissful a sound, indeed, that I forgive the occasionally juvenile limerence of their lyrics.

People: Mark Diacono

Mark’s a food and gardening writer who I have followed for a while. We share a love of the world’s best football team. But recently, I’ve been drawn back to his work because of what he started here on Substack: The Imperfect Umbrella with Mark Diacono. Underneath that canopy, he is writing about the act of writing a book: ‘Taking you from the lightbulb idea moment through the whole process of trying to get a book published, along with the writing process, insights from publishers/authors and more…’. As someone who worked inside of food publishing for a long time I know the value and quality of the insights he shares and if you’re thinking of writing a book (any book) then you’ll almost certainly find much to enjoy and much to learn by following his journey.

Forthcoming events

Phone photography masterclasses on Saturday 17th December and Saturday 21st January.

Join me, via Zoom, for the last phone photography workshop for 2022 or the first workshop of 2023. If you’re keen to improve your photographic and styling skills, either for personal or business development, then the workshop is an effective way to start. Ten per cent of each £80 booking fee is donated to The Trussell Trust (over £2,000 since these donations began). Follow this link for more info on what the course entails. Free places are available each workshop to those who cannot afford to pay.

Cornflakes, too, when I was a young child, with warm milk and heaped teaspoons of sugar. Nostalgia still hits very hard at the thought of that bowl of sweet cereal confection today. I worked on the UK edition of Christina Tosi’s Momofuku Milk Bar book some twenty-plus years after becoming an adult. Discovering her cereal milk recipe and then making and tasting the panna cotta born of that sugary base was an almost tearfully blissful experience. The roots of the word ‘nostalgia’ translate from the German word, ‘Heimweh’ (homesickness). That word comes from the Greek words, ‘nostos’ (return home) and ‘algos’ (pain). The pain is literally something that pulls at the heart and makes us wish to return to that moment. Nostalgia is less the pleasure that the heart has known, but a desire to revisit the sweetness of a pain which it has felt.

I’m browsing your archive Matt and this is so lovely. I’m reminded of the marmalade toast and cup of milky tea a kind nurse handed me immediately after the birth of my daughter. I doubt I will ever enjoy a plate of food that much again.

This is very beautiful writing, dear Matt. Words to luxuriate in. Details abound. Gently expressed but providing the spark for further enquiry. The walk through Umberto Eco's library is astonishing and I love the descriptions of the books we all acquire. Very lovely to lose oneself in this quality of writing, particularly knowing that you ration us to monthly morsels and so the exquisite wait for the next serving of your musings is as tantalising as the words themselves. Bravo. So glad you are writing. B